You know that first mile where you sound like you’re auditioning for a freight train? Been there. Truth is, most runners think breathlessness means they’re “out of shape.” Nope. It means your breathing game’s untrained.

Breathing while running isn’t just “inhale, exhale.” It’s rhythm, posture, muscle coordination, and mental control — all working together (or not) to keep your legs moving and your brain from panicking.

I’ve coached runners who couldn’t get past 400 meters without gasping… and six weeks later, they were breezing through 5Ks without thinking about their breathing.The difference? They learned how to train their breath like they train their legs.

This guide is your blueprint. No fluff. No magic gadgets. Just science, experience, and proven drills to make your breathing smoother, your runs faster, and your recovery quicker.

I’ll break it down so you know exactly how to breathe on easy runs, hill climbs, and race-day sprints — and how to fix things mid-run when it all goes sideways.

By the end, you’ll know how to use your breath as a tool — to control pace, calm your mind, and push harder without falling apart.Does it like a good idea? Then let’s get to it.

Table of Contents

- Why Breathing Feels So Hard When You Start Running

- The “first-mile wall” and what’s really going on in your body

- Anxiety, posture, and breath-holding traps

- Breathing Mechanics 101

- Diaphragm function and posture alignment

- Why upper-chest breathing kills your endurance

- Nose vs. Mouth Breathing: When to Use Each

- Benefits of nasal breathing

- The power of mouth breathing in high effort

- Combo breathing for versatility

- Rhythmic Breathing: Syncing Breath with Stride

- 3:2, 2:2, and other patterns explained

- How to prevent side stitches with foot-switching exhales

- Breathing by Effort Zones

- Zone-based breathing cues for training and racing

- Breathing Drills for Runners

- Diaphragm training (crocodile, balloon breathing)

- CO₂ tolerance drills

- Resisted breathing techniques

- Breathing Strategies for Tough Conditions

- Cold weather

- Heat and humidity

- Altitude

- Trail running

- Mid-Run Rescue Techniques

- Cue words and mantras

- Quick resets for panic breathing

- Smart walk breaks

- Race-Day Breathing Plan

- Pre-race breath priming

- First-mile effort gating

- Mid-race breathing control

- Final push strategies

- Post-Run Breathing for Recovery

- Calming the nervous system

- CO₂ dump and relaxation drills

- Mindset: Coaching Yourself Through Breath Fatigue

- Treating breath as feedback, not failure

- Final Takeaways

- Breath as a skill you can train

- Building calm, focus, and power

You’re Not Broken. You’re Just New.

I want to be clear from the get-go:

feeling breathless when you start doesn’t mean you suck.It means your body’s learning. You’re not “out of shape” — you’re just untrained to breathe under pressure. And breathing under load? It’s a skill. Just like pacing. Just like

cadence. Just like any part of running.

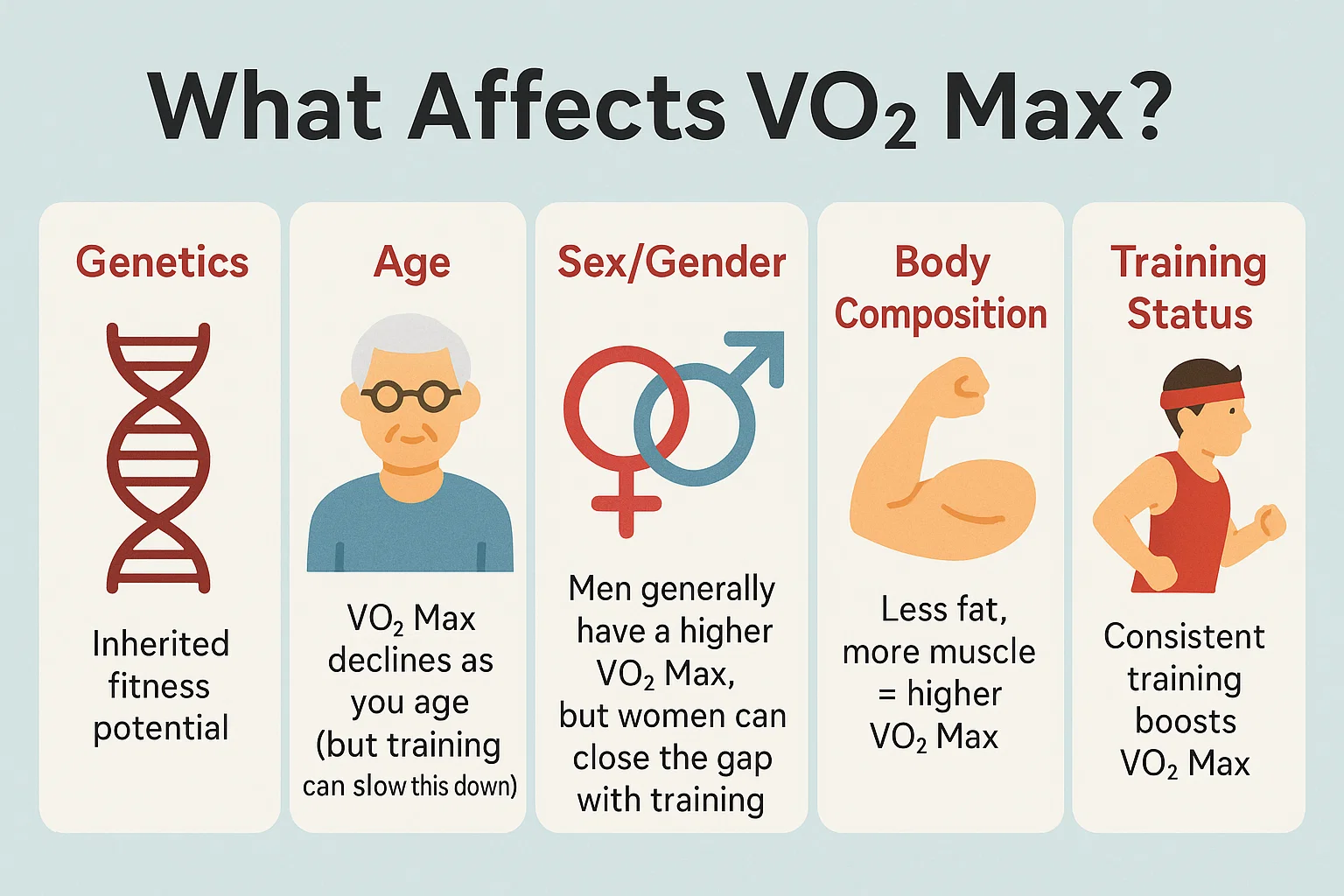

You don’t need special gadgets or a fancy

VO₂ max score. You need reps. You need patience. You need to breathe, shake it off, and keep moving. Over time, that wild, out-of-control breathing turns into a rhythm — one you can ride like a wave.

Nose vs. Mouth Breathing While Running – What Really Works?

Alright, real talk—there’s been a lot of buzz lately in running circles about whether you should

breathe through your nose or your mouth while pounding the pavement.You’ll hear diehards on both sides preaching like it’s religion. But here’s the truth from a coach who’s been in the trenches:

It depends. Yeah, I know, that’s not a sexy answer. But stay with me.

There’s a time and place for each breathing style. Sometimes you’re better off pulling air through your nose like a Zen monk.Other times, you’re gasping like a freight train through your mouth—and that’s totally okay.Lemme explain what mean a little more:

Nose Breathing – The Calm Beast

Breathing through your nose has some killer benefits—especially on

easy runs or warm-ups.

- Air gets filtered and warmed up by the little hairs and mucus in your nostrils. That’s good news for your lungs, especially on cold days.

- It chills you out. Nose breathing switches on your parasympathetic nervous system—that’s the “rest and digest” mode. Translation: slower heart rate, less stress, more control.

- Better CO₂ tolerance. When you breathe slower through your nose, your body gets used to having more carbon dioxide in the system. That may sound scary, but it actually helps you push harder before hitting that “I-can’t-breathe” wall.

- Oh, and nitric oxide. It’s made in your sinuses when you breathe through your nose, and it helps widen your blood vessels so oxygen moves more efficiently. Cool, right?

But here’s the rub: at higher speeds or on hills, your nose just can’t keep up. The airflow isn’t enough. You’ll feel like you’re suffocating if you try to stay strictly nasal during a hard sprint. I’ve nearly passed out a few times because I was stubborn about nose breathing during intervals. Don’t make my

mistake.

Also, if you’ve got allergies, congestion, or just tight nasal passages—it’s gonna be a tough sell.But the good news? You can train it.

Mouth Breathing – The Power Move

Let’s not demonize mouth breathing. It’s not lazy. It’s not cheating. Sometimes it’s just what your body needs—especially when things get spicy.

- You can pull in way more air. The airway through your mouth is bigger, so at high effort, this becomes essential.

- Great for hard exhaling. Ever notice that “whoosh” when you’re pushing through a tempo? That’s your body dumping carbon dioxide fast. It’s a relief valve.

- Crucial for intense stuff—think hills, sprints, races. This is when you need all the oxygen you can get, as fast as possible.

Downside? Mouth breathing lets in cold, dry, unfiltered air—straight to the lungs. That can irritate your airways and

trigger coughing fits or even bronchospasm if you’re sensitive. Also, your mouth dries out like the Sahara, which nobody loves.

And there’s the panic factor. Ever notice how mouth breathing can feel a little frantic? It’s the same kind of fast breathing you do during a stress spiral. So yeah, it’s effective—but it can send mixed signals to your brain.

Nose + Mouth Combo – The Smart Play

Now this is where things get interesting. You don’t have to choose sides. The smartest runners I coach (and I try to be one myself) use a

combo approach.

- Inhale through the nose, exhale through the mouth. It calms you down, keeps your breathing steady, and still lets you dump CO₂ easily.

- Mix and match depending on the terrain. Downhill? Stay nasal. Flat? Try to nose-breathe if you can. Uphill sprint? Let the mouth take over.

Think of it like shifting gears in a car.

One of my go-to moves is starting my

long run with nasal breathing, then letting the mouth come in as I pick up pace. It’s a smooth transition, not a flip-the-switch kind of thing.

But here’s the deal: this takes practice. At first, you’ll probably forget, or feel like you’re overthinking it. That’s normal.But give it a few weeks, and you’ll start switching back and forth naturally—like second nature.

Rhythmic Breathing: How to Sync Your Breath with Your Stride

Ever find yourself out on a run and notice your breathing syncing up with your footsteps? Like, left-right-inhale, left-right-exhale—it’s not just some happy accident.That’s called

rhythmic breathing, and dialing it in can change the way you run.It helps your effort feel smoother, keeps your pacing steady, and believe it or not, might even save you from those nasty

side stitches or overuse injuries.

Let’s break this down in plain English—no lab coats, just stuff that actually helps when your lungs are on fire halfway up a hill.

2:2 — The Go-To for Getting After It

This one’s a classic. Inhale for 2 steps, exhale for 2 steps. So, you’re breathing in on left-right, then out on left-right again.It’s quick, tight, and a lot of runners naturally fall into this during

tempo runs or solid effort runs—not quite race-pace, but definitely working.

But here’s the kicker: because it’s even (2+2=4), you always start your inhale and exhale on the same foot. That matters—hang tight, we’ll get to why.

3:2 — The Sweet Spot for Most of Us

This one’s my favorite, especially on steady runs. Inhale for 3 steps, exhale for 2. So you’re pulling in air on left-right-left, then letting it out on right-left.Total of 5 steps per breath cycle, which means your exhale lands on a different foot each time. That’s huge.

A ton of coaches love this pattern—it gives you a little longer inhale, which can help get more air in, and by flipping sides each cycle, you’re not hammering one side of your body with all the impact.

4:4 — Chill Mode

Four steps in, four steps out. You’re cruising here—think recovery jog or

warm-up shuffle. This pattern’s too slow for anything serious, and if you try it at a faster pace, you might feel like your lungs are suffocating from the inside.A coach I worked with once said never go slower than 3:3 unless you’re basically walking. And they were right—CO₂ builds up fast if you’re holding your breath too long.

Other Patterns (aka What Sprinters Do)

You’ve got 3:3 (inhale 3, exhale 3), 2:1, 1:2, and even 1:1. These short, fast rhythms are for when you’re redlining—like last 400 meters of a race, or

sprint intervals. Not something you want for your 10-miler, unless you’re looking to hit the wall by mile 1.

Why Bother With Breathing Patterns?

Here’s the part most people don’t realize: exhaling is when your core is at its weakest. Your diaphragm relaxes, your body’s a little looser.So if you

always exhale when your right foot hits the ground, that side’s taking more of the pounding when you’re least braced. That’s a recipe for side stitches—or worse, long-term imbalance and injury. And that’s why I briefly mentioned this before.

A pattern like 3:2 (odd number of steps) switches the foot you exhale on every cycle.It’s like giving each side of your body a turn under pressure. Smart, right?

Research backs this up: exhaling on alternating feet distributes the impact more evenly.

So yeah, breathing rhythm isn’t just about getting air in—it’s about how you

carry that air and use it to keep your body balanced over the long haul.Aside injury, here are more reasons breathing this way rocks:

Helps You Hold Pace Without Thinking

Ever notice how music with a steady beat can help you keep pace? Rhythmic breathing does the same.It becomes like a built-in metronome. Once you find your flow, it’s easier to stay steady without checking your watch every 30 seconds.

I know if I switch from a 3:2 to a 2:2 without meaning to, I’ve probably sped up or hit a hill. That rhythm shift becomes an early warning system—“Hey dummy, you’re working harder than you think.” From there, you can either ease up or lean in, depending on the goal for that run.

Plus, it helps clear your head. There’s something almost meditative about syncing your breath to your stride. It keeps you present. In the zone. Especially on long

solo runs, this trick alone has saved me from mentally checking out and slogging through the miles.

Say Goodbye to Side Stitches

Those brutal, sharp pains under your ribcage? Often they show up when your breathing is erratic—or when you’re always exhaling on the same foot. That strain on one side of your diaphragm builds up until it screams at you.

Switching up your breathing rhythm is one of the best mid-run fixes.Try this: if you feel a stitch coming on, switch to a deeper rhythm like 3:3 or even 4:4 temporarily, and make sure you’re exhaling on the

other foot than you have been.It won’t always fix it instantly, but in my experience, it helps more often than not.

Breathe Smarter by Effort Zone (Not Just Vibes)

Breathing isn’t just “inhale, exhale, repeat.” It changes with effort — and learning how to

read your breath is one of the most powerful tools you’ve got.

Let’s break it down into 5 effort zones, runner-style:

Zone 1 – Super Easy / Recovery

How it feels: Like you’re just floating. Barely breathing hard, full conversation possible, probably nose-breathing the whole time.

Breathe like: 4:4 or 3:3 (inhale 4 steps, exhale 4). Deep belly breaths, all through the nose if you can.

Pro tip: If you’re mouth-breathing here, you’re going too fast for recovery. Use these runs to

train your diaphragm — better CO₂ tolerance, better breath control later.

Zone 2 – Easy Aerobic

How it feels: You’re working, but could still chat in short sentences. It’s your bread-and-butter pace — your “go-to” cruise mode.

Breathe like: Nose in, mouth out works great. 3:2 or 3:3 step rhythm. Think “easy in, easy out.” Deep, steady, no rush.

Coach’s note: Master breathing in Zone 2, and your endurance skyrockets. This is where running economy gets built.

Zone 3 – Tempo / Threshold

How it feels: “Comfortably hard.” You can talk… barely. Breathing starts to get heavier, more noticeable, but not wild.

Breathe like: Mouth in, mouth out. 2:2 rhythm is solid here. Still deep and full, not panting.

Reality check: This is the highest zone where you can still control your breath

on purpose. Past this? Your body takes over. So keep the rhythm here — or risk spiraling into the gasping zone.

Zone 4 – Hard (VO₂ Max)

How it feels: Legs burning, lungs pumping like bellows. You’re not talking. You’re surviving.

Breathe like: Mouth only, and probably unpatterned. Could be 2:1, 1:2, whatever your body demands. Focus on

deep, not shallow — fight the panic pant.

One trick: Pursed-lip exhales can help slow the out-breath and keep you from hyperventilating. Blow out like you’re puffing through a straw.

Zone 5 – Max Effort / Sprint

How it feels: Like you’re breathing through a straw while sprinting from a bear. Total gasping, max effort, everything burns.

Breathe like: Whatever keeps you going. This isn’t about patterns anymore. Just don’t hold your breath — that’s a fast ticket to burnout.

Pro tip: Sprinters often do one big inhale pre-race, then hammer out powerful exhales with each stride. For mid-distance stuff (200m to 800m), it’s all about quick, explosive air exchange.

Your Breath Doesn’t Lie: Learn to Read It

Want to know one of the simplest but most underrated tools to gauge effort? Your breathing.

Forget the fancy

heart rate straps and techy graphs for a second—your breath is the OG training partner. It tells you the truth in real-time, no lag, no nonsense.

I coach runners to use something called the “talk test” or even better, the “nose test.” Here’s how it plays out:

- Nose-breathing and chill? You’re cruising in Zone 1 or 2—easy running. This is the zone where you’re relaxed, conversation flows, and you could run forever.

- Mouth starts opening up but you can still chat in short bursts? That’s Zone 3. Tempo pace. It’s work, but manageable. I call it “comfortably uncomfortable.”

- Can’t speak more than one or two words without gasping? Now you’re in Zone 4. That’s threshold territory—hard, gut-check stuff.

- Straight-up gasping like a fish out of water? Zone 5. All-out. That’s your VO₂ max party—if you can call it that.

These shifts line up exactly with your physiological thresholds.Around Zone 2-3, you cross into that aerobic threshold zone—breathing ramps up and that chill conversation? Gone.Once you’re in Zone 4,

lactate builds, and your breathing turns sharp and loud.Zone 5? That’s a full-blown lung brawl.

How This Plays Out on a Real Run

Let me walk you through a run I’ve done—and probably tortured a few clients with too.

- Warm-Up (Zone 1): Easy jog. I’m nasal breathing with a 3:3 pattern. Barely hear myself breathe. Just loosening up.

- Steady-State (Zone 2): Breathing gets a bit louder, I’m at 3:2 now. Still comfy, maybe exhaling through the mouth. Can talk if I want.

- Tempo Block (Zone 3): Things heat up. I’m now 2:2, breathing fully through my mouth. It’s sustainable—but it’s work. Legs ticking, brain focused.

- Hill Repeats (Zone 4): Just 1-minute efforts, but holy hell. Within seconds, my breath flips to 2:1 or worse. By the top, I’m huffing. On the jog down? I track recovery—3:3 comes back, that tells me I’m bouncing back well.

- Final Sprint (Zone 5): 100 meters all-out. I don’t even notice my breathing pattern—it’s just rapid-fire inhale-exhale. Pure grit.

And that’s the beauty of it—your breath adjusts with the effort. If you’re aiming for a

Zone 2 recovery run but you’re breathing like you’re in Zone 3? You’re going too hard. Ease off.On the flip side, if you’re doing intervals and not hitting that ragged-breathing Zone 4/5 territory? You’re sandbagging it, my friend. Time to push.

Wanna Race Smarter? Use Your Breath

Here’s a solid trick I teach before races: Mentally walk through your “breathing plan.”

For example, first 5 miles of a half? Stay in that steady 2:2 or 3:2 range. If you feel yourself creeping toward 2:1 breathing too early—back off. Save that pain cave for mile 11+. Having a breathing cue like this keeps you honest when adrenaline tempts you to go out hot.

Fitness = Better Breathing, Faster Recovery

Here’s where it gets cool: as you get fitter, your breathing changes.

- You’ll stay in lower zones at faster paces. A beginner might be huffing (Zone 3) at 7 min/km. But give it a few months of smart training? That same pace will feel like Zone 2—easy breathing, all day long.

- You recover faster. A seasoned runner can hammer a Zone 4 interval and bounce back to Zone 2 breathing within a minute. Newer runners? Might stay in that heavy Zone 3 zone for 3-5 minutes trying to catch up.

Your breathing becomes a sign of progress—like your personal race report card.

How to Breathe Better When You Run

Here’s the truth: breathing while running isn’t some magical thing you’re either good at or not. It’s a skill. Like hill repeats or lifting weights — it gets better when you train for it.

And no, trying to “breathe harder” on your runs doesn’t do the trick.If anything, that just makes you feel more gassed and stressed. Instead, you gotta train your breathing system the smart way. Build stronger breathing muscles.

Increase your lung capacity. Improve how well you handle CO₂.

Sound fancy? It’s not. You just need the right drills — simple stuff you can mix into your weekly routine a few times.Stick with it, and in a few weeks you’ll probably notice you’re not sucking wind as much mid-run.

Let’s break it down.

1. Train Your Diaphragm

Think of your diaphragm as your running engine’s core. It’s the muscle that drives your breathing — and yep, you can actually make it stronger and more efficient.

A stronger diaphragm = easier breathing, better posture, less fatigue on long runs.

Here are two killer drills I use and recommend to every runner I coach:

Crocodile Breathing – Belly Breathing, The Right Way

This one’s dead simple and weirdly calming.

Lie face down, hands under your forehead like you’re taking a nap on the trail. Now breathe into your stomach — not your chest. You’ll feel your belly pushing into the floor if you’re doing it right.

How to do it:

- Inhale through your nose for about 3–4 seconds

- Let your belly expand into the ground

- Exhale through your mouth for 4–6 seconds

- Keep your shoulders and chest relaxed

Do this for 5–10 minutes. That’s it.

It retrains your body to lead with the diaphragm — not the upper chest. And it’s great before a run to calm your nerves, or on off days as a little breath work + core reset. I’ve had runners tell me they actually start breathing better without thinking about it after a couple weeks of this. Their posture improves too — because guess what? A working diaphragm supports your spine and keeps your form tight.

Bonus: It’s great for calming down pre-race jitters and even helps ease lower back tension.

Balloon Breathing – Don’t Laugh, This One’s Legit

I know — it sounds like a kid’s birthday party move. But trust me, balloon breathing is no joke.

Blowing up a balloon makes your abs and diaphragm work hard — especially when you control the exhale. It teaches you to breathe

out completely, which most runners suck at. And when you empty the lungs fully, you make more space for your next breath. More oxygen in = better performance.

How to do it:

- Lie on your back, knees bent — or get fancy and do the “90/90” position (feet on a wall, hips and knees at 90°)

- Inhale deep through your nose into your belly

- Exhale slowly into the balloon

- Fight the urge to rush it — make it a smooth, steady blow

- When your lungs are empty, pull the balloon out (don’t breathe back in from it)

- Repeat 5 times

You’ll feel your abs tremble a bit. That’s a good sign — they’re working.

This move also fires up your deep core muscles (hello, transverse abdominis), which means better posture and less sloppy form on the back half of long runs.

Physical therapists even use this one for back pain and breath rehab. I use it on recovery days or during strength sessions. Start with an easy balloon (those cheap party ones work fine). Once you get stronger, you can do more rounds or graduate to tougher balloons.I’ve shared more drills

here.

Functional Respiratory Capacity (FRC) Drills

Alright, here’s the deal. Most runners train their legs, their heart, their pace. But how many of us actually train our lungs? Yeah, that’s right — your breathing muscles are muscles. You’ve got to work them too if you want to unlock that next gear.

“FRC” basically means making your lungs work better — pulling in more air when you need it, and pushing it out strong and steady. There are two types of drills I swear by:

resisted breathing and

breath holds.

Resisted Breathing

You’ve probably seen those funky-looking gadgets like the PowerBreathe or TrainingMask. They make it harder to breathe in — kinda like sucking air through a coffee stirrer.That resistance? It forces your lungs and diaphragm to work harder, and that makes them stronger.

But hey, if you don’t want to drop cash on gear, you’ve got options:

- Pursed-Lip Breathing – It’s simple. Breathe in through your nose, then exhale slowly through tight lips — like you’re trying to blow out a candle in slow motion. That back-pressure makes your muscles work for it. It’s not just a runner hack — they use this in pulmonary rehab to help folks with real lung issues.

- Straw Breathing – Grab a regular straw (thin ones work best) and breathe through it for a minute or two. That’s it. Just normal breathing — but harder. Don’t push it to the point of feeling lightheaded. A minute or two is enough. I use this as a warm-up sometimes before harder sessions. Gets the diaphragm fired up.

And it’s not just feel-good fluff.

Research shows that resisted breathing — especially done daily at high resistance — can boost VO₂ max and reduce breathlessness during training.Basically, your lungs stop tapping out so soon. You become harder to fatigue. Like giving your lungs their own strength workout.

Want to keep it simple? Try:

- 10 slow pursed-lip exhales

- 10 straw inhales

- Rest with regular breathing in between so you don’t hyperventilate

- Repeat for a few rounds

That’s lung training, DIY style.

Breath Holds – Build CO₂ Tolerance and Stay Calm Under Pressure

Now this one’s a bit weird — but stick with me.

Holding your breath helps your running. Yeah, you read that right.

It’s not about turning blue or passing out (please don’t). It’s about training your body to handle more carbon dioxide (CO₂) and use oxygen more efficiently. That’s big-time for runners, especially when the effort cranks up and breathing gets heavy.

Here’s one I love:

Exhale-Hold Drill

- Breathe in normally

- Breathe out normally (don’t force it all out)

- Once your lungs are about halfway empty, hold your breath

- Stay there until it feels “strongly uncomfortable” — not panic mode, just a solid urge to breathe

- Then go back to calm nose breathing for a couple minutes

Do this for 3-5 rounds.Lemme explain why does this seem to work.

During the hold, CO₂ builds up. That forces your diaphragm to contract, even without breathing. That twitchy “gotta breathe” feeling? That’s your diaphragm flexing.Over time, this builds strength and endurance, and also retrains your chemoreceptors (those little sensors that freak out when CO₂ rises) to chill out. That means you’ll stay calmer, longer, even when things get hard mid-run.

A bonus? Runners have used a “walk-and-hold” trick — walk while holding your breath after an exhale. Track how many steps you can go. Over time, it increases. More steps = better tolerance.

Another one I dig:

Box Breathing – 4 seconds in, 4 hold, 4 out, 4 hold. It’s like breathing meditation. Helps with lung control and mental focus. Elite athletes and freedivers swear by it — and if it helps them dive 100 feet deep on one breath, it can sure as hell help us on

hill repeats.3. CO₂ Tolerance – Stop Gasping, Start Breathing Smarter

We already dipped into this with breath holds. But let’s take it a step further.

You know what changed the game for me?

Nasal-only training.

That’s right — close your mouth. Literally.

When you breathe only through your nose during a run, you automatically start building CO₂ tolerance.Why? Because you’re breathing slower. You can’t blow off CO₂ as fast, which means you’re forcing your body to work with slightly higher levels of it. It feels tough at first — almost like you’re suffocating. But that’s the point.

Start small:

- 5–10 minutes nasal-only in an easy run

- Or try alternating: 5 min nasal, 2 min normal

- Build from there

Over time, you’ll notice something wild: your breathing rate drops, you feel less frantic on hills, and you stop hyperventilating.Plus, nasal breathing boosts nitric oxide — that’s a natural blood vessel opener, which means better oxygen delivery to your muscles.

For me, I started with nasal breathing on recovery runs. It sucked for the first week. But after a while? I could cruise at a solid pace without feeling like I was dying. It’s low-key one of the most underrated breathing drills in the game.

CO₂ Tolerance: Train It Like You Train Your Legs

Alright, if you’ve ever felt like you’re sucking wind on every run—even the easy ones—this part’s for you. A lot of runners don’t realize that their problem isn’t lungs that aren’t strong enough… it’s lungs that aren’t trained to deal with rising CO₂ levels.

That “air hunger” feeling? It’s usually not about low oxygen. It’s your body panicking because CO₂ is building up in your system—and you haven’t taught it that it’s okay. That’s where CO₂ tolerance drills come in.

Breath-Hold Workouts (A.K.A. What Freedivers Do… That Runners Should Too)

Some folks use what are called

CO₂ tables—these are common in freediving circles, but they’re gold for runners too.Here’s how it works: you hold your breath for a set time (say, 30 seconds), then breathe normally for a minute.Then hold for 40 seconds. Breathe again. Then 50 seconds. And so on. You’re either making the hold longer or the rest shorter.

Apps like

Breathwrk,

Oxygen Advantage, or even freediving apps can guide you through these safely.But honestly, you don’t need to overthink it.A simple version? Hold your breath after an exhale until you feel moderately uncomfortable, then breathe normal for a minute. Repeat five times. Each week, try to go a bit longer or shorten that recovery time.

Important: Always do this stuff sitting or lying down. Don’t be the guy who passes out mid-run trying to prove something.

Long Exhales = CO₂ Tolerance + Mental Calm

Ever find yourself panting through your mouth on a run, like a dog in July? Chances are, you’re not exhaling fully. That’s a sneaky sign of low CO₂ tolerance.

Here’s the fix:

focus on the exhale. I’m talking about pushing the air out—three-second exhale at an easy pace, maybe even longer if you’re just jogging. This helps your body get used to that slightly uncomfortable CO₂ rise… and it chills your nervous system at the same time.

There’s science here too: long exhales fire up your

vagus nerve, which tells your body to calm the heck down. That’s why some coaches (especially those who work with runners training at altitude) really hammer this.At elevation, you’re naturally breathing faster, and CO₂ can tank—so exhaling well becomes even more important. But guess what? It matters just as much at sea level.

I tell my runners: when in doubt, sigh it out. A good, strong exhale mid-run can reset your breath and your brain.

4. Breathing Drills: Where They Fit In Your Training

Knowing the drills is one thing. Actually doing them? That’s the work.Here’s how to slide these into your week without turning it into some massive project.

Before You Run (Warm-Up the Right Way)

Your legs aren’t the only thing that need warming up. If you go from couch to running in five minutes without getting your breath ready, don’t be surprised when you’re panting before the end of your block.

Try this: do 2–5 minutes of breath-focused warm-up. A couple favorites:

- Crocodile breathing or belly breathing to get the diaphragm in play.

- If you’re nervous or tend to go out like a maniac, do a few rounds of 4-7-8 breathing: inhale 4 seconds, hold 7, exhale 8. Calms the nervous system and slows the heart rate.

I’ve even started this while I’m lacing up

my shoes—deep inhale, big yawn, a few stretches to open the chest. You’re not just prepping muscles. You’re flipping the switch in your breathing system, so it’s ready when your feet hit the pavement.

During Your Run (Turn Runs Into Practice Sessions)

You don’t need to make every run a breathing drill, but sprinkle ‘em in. For example:

- Use Zone 2 runs as nasal-only training time.

- Every 20 minutes of a long run, throw in 2 minutes of nose-only breathing.

- During strides, try a 2:1 inhale:exhale pattern—get used to fast, controlled breathing.

- Running to a beat? Try syncing your breath to the music. It’s weirdly effective.

Even just

picking a hill and saying, “Okay, I’m locking into 2:2 breathing here,” can train your system to stay calm under pressure. Do this enough, and breathing becomes automatic—like shifting gears.

After You Run (Breathe Your Way to Recovery)

Hard run done? Don’t just stop and scroll Instagram. Give your breath two minutes.

Here’s what I use for recovery:

- Breathe in through your nose for 3 seconds.

- Exhale for 6+ seconds, slowly.

- Do that for 2–5 minutes as you walk or stretch.

Or go with

box breathing—inhale 4, hold 4, exhale 4, hold 4.

Even better: lie on your back, feet up on a wall, and do deep belly breaths. That drains your legs and sends your nervous system into chill mode. Feels amazing. Faster recovery, lower heart rate, better digestion… all from a few mindful breaths.

Make It a Game. Make It Yours.

Breathing doesn’t have to be boring. You can test and track your progress:

- Try the BOLT score (Body Oxygen Level Test): see how long you can hold your breath after a normal exhale until you feel the first real urge to breathe.

- Try “breath holds while running”—see how many steps you can go after an exhale (safely!).

- Or just track your real-world wins: “When I started, I could only nose-breathe at 7:00/km. Now I can do it at 6:15/km.” That’s progress.

Some runners love using gadgets—there are devices and apps that gamify breath control. Not necessary, but hey, if it keeps you consistent, go for it.

Breathing Drills You Can Actually Use

Alright, time to get hands-on. This isn’t theory anymore — this is your breathing toolbox. These drills? They’re your pre-run warm-up, mid-run reset, and post-run breath control. Think of them like strength work for your lungs and a mental reset button rolled into one.

You don’t need to do all of ’em every time — just pick what fits your day. Feeling jittery before a race? Try the calming ones. Breathing like a steam engine halfway through your long run? Pull out the mid-run tricks. Let’s break it down.

Pre-Run: Get Your Breath Right Before You Even Start

A calm start = a stronger run. If your lungs and mind are chilled out at mile zero, you’re already winning. Here’s what to try:

Crocodile Breathing (aka Wake Up That Diaphragm)

This one’s a classic — and weirdly awesome.

Lie on your belly, hands stacked under your forehead, and just breathe. Feel your stomach press into the ground on every inhale. That’s your diaphragm getting to work.

Can’t lie down in public (been there)? No problem. Bend over like you’re catching your breath, hands on knees, and focus on sending your breath to your belly. Your hands should feel that rise.

Do this for 1–2 minutes. Boom — your body’s like, “Oh yeah, let’s use the diaphragm today.”

4–7–8 Breathing (Kill Pre-Run Anxiety)

If you’re the type that gets revved up before runs — like your heart’s sprinting before your legs even move — this one’s gold.

- Breathe in through your nose for 4 counts

- Hold it for 7

- Exhale through your mouth for 8

- Do 4–5 rounds

This slows your breathing, your heart rate, and your racing brain. I’ve had runners go from borderline panic to totally composed with just a minute of this. If 7 and 8 feel too long? Adjust it — maybe do 3-5-6. The goal is to extend the exhale and chill your system.

Great before races, workouts, or even stressful group runs.

Box Breathing (Center Yourself Like a SEAL)

Used by Navy SEALs. Yep. It’s that good.

Inhale 4

Hold 4

Exhale 4

Hold 4

Repeat.

Feels like meditation, but with more edge. Even just a minute of this can help you feel focused and grounded. If you do this while doing some light stretching or drills? You’re basically unlocking a calm, sharp version of yourself before the run even starts.

Bonus tip: Heading out into freezing weather? Do a few rounds of slow nasal breathing indoors first. It preps your airways for that cold slap of air.

Mid-Run: Drills to Help You Breathe Better While You’re Moving

You don’t need to wait for something to go wrong mid-run to use these — but they’re especially clutch when things start to feel off.

2-Minute Nasal-Only Drill

Pick a stretch in your run (early miles are best), close your mouth, and breathe only through your nose for 2 minutes.

Yeah, it’ll probably slow you down. That’s the point.

It trains diaphragmatic breathing and shows you if your “easy pace” is actually easy. If nasal breathing feels impossible? You’re going too hard.

Stick with this once or twice a week, and by the end of a training block, you’ll notice: “Dang, I can do this for 10 minutes now.” That’s your aerobic system leveling up. Plus, it trains your CO₂ tolerance (remember, that’s what actually makes you feel breathless).

Don’t tough it out if it gets super uncomfortable — switch back to normal breathing when needed. This is training, not punishment.

Stride Cadence Breath Match (aka Breath-Music for Your Legs)

This is where breathing meets rhythm.

Try matching your breath to your footsteps. On an easy run, go with a 3:2 pattern — inhale for 3 steps, exhale for 2. Say it in your head: “Inhale, two, three. Exhale, two.”

If you’re working harder, maybe shift to 2:2. It’s not about being perfect — it’s about syncing your breath with your stride and feeling connected.

I’ve coached runners who used this to break through mid-race panic. Others say it helps fix form issues — like realizing they’re leaning weird or slamming one foot harder than the other.

So yeah, it’s a breathing drill… but also a sneaky form check.

Terrain-Based Breathing Drill (Shift Your Gears)

This one’s actually kinda fun—like breathing with intention instead of just “getting air.”

As you hit different terrain,

consciously change your breathing pattern to match. You’re teaching your body to handle shifts in effort without flipping out. Here’s how I do it:

- Flat road? Try 3:3 (inhale for 3 steps, exhale for 3).

- Climbing a hill? Drop to 2:2 or 3:2. Time to bring in more oxygen.

- Going downhill? Smooth it out—maybe 4:4 or back to 3:3.

If you’re doing

fartlek runs (you know, speed play), match your

faster breathing pattern to the surge, then slow it down during the float. It keeps you present, helps with pacing, and honestly, just makes you feel like you’re in control.It’s also a great mental check-in. Are you panicking on hills? Holding too much tension? This kind of “breathing play” keeps your brain in the run, not wandering off to your to-do list.

You don’t have to breathe like this all the time—just sprinkle it in. Like a rehearsal for when you really need to control your breath in a race, or when things get tough and panic creeps in.

Mid-Run Reset When Anxiety Hits

Ever had one of those runs where your heart rate spikes for no reason? Or you trip, get startled, and suddenly feel your brain spiraling?

Yeah, I’ve been there.

Here’s what I tell my runners:

Don’t try to tough it out. Reset.

Try this:

- Belly breathing: 10 slow, deep breaths. Count the inhale and exhale. All in through the nose if you can.

- Or do cadence breathing: Count steps to 30 while breathing slow and steady, then do it again. It anchors your brain.

- Some runners literally name their breath cycles—“Breathing in strength… breathing out stress.” Sounds cheesy, but when your thoughts are racing, even a simple mantra can work like magic.

Post-Run Breathing Drills – Because Recovery Starts With Breath

The run’s done. You’re sweaty, heart’s thumping, maybe feeling a bit dizzy or just “off.” Now’s the time to flip the switch—bring your body out of “go” mode and into recovery.

These post-run breathing drills? Absolute gold.

Parasympathetic Reset (Long Exhale Drill)

This one’s simple and super effective:

- Inhale through your nose for 3 seconds

- Exhale slowly for 6 or more (mouth or nose, doesn’t matter)

Do that for a minute or two. Feel that heart rate settle? That’s your vagus nerve doing its thing. Want to crank the effect up? Exhale with a soft “Haaa” or try humming—both are known to

stimulate that calm-down switch in your nervous system.

And make sure you’re breathing with your belly, not your chest. That deep, low breath helps with nausea or post-run cramps by restoring the CO₂/O₂ balance in your system.

Nose Inhale, Big Mouth Sigh (CO₂ Dump)

Sometimes after a hard effort, your lungs feel like they’re still holding onto the run. Try this:

- Big breath in through your nose

- Long, exaggerated sigh out the mouth (think tired sigh, not sharp exhale)

- You can even bend forward as you breathe out to help push the air out of your gut

Do this 3–5 times. It helps dump trapped CO₂, clears out the heavy feeling, and

mentally signals “effort’s over.” Swimmers use this all the time post-race. Works just as well for runners.

Legs-Up Breathing (Gravity-Assisted Recovery)

Got a wall nearby? Lie down, kick your legs up, and just chill.

- Do slow belly breaths—whatever pattern feels calming

- Even 2–3 minutes here gets the blood moving out of your legs, which helps flush waste and reduce soreness

I do this after every long run. Sometimes I close my eyes, breathe deep, and let the day melt off me. Cheap, easy, and wildly effective. It’s also the best cool-down pose if you’re prone to post-run headaches or that drained-zombie vibe.

5-Minute Breath Meditation (Guided Reset)

If you’ve got a little more time and want to go deeper, try this DIY 5-minute breath meditation:

- 1 min of slow belly breathing

- 1 min of box breathing (inhale-hold-exhale-hold, 4 seconds each)

- 1 min of exhale + relax (tense and relax muscle groups with each breath)

- 1 min of gratitude breathing (think of something positive with each inhale)

- 1 min back to natural breathing, eyes closed, just let it settle

Yeah, it sounds a little crunchy, but I swear it works. And if you’re a headcase like me after a race or workout, it gets you grounded fast.

Breathing Tips for Tough Running Conditions

Running doesn’t always happen on a breezy spring morning. Sometimes it’s cold, windy, or at altitude—and that can mess with your lungs. But if you prep for it, you’ll suffer less and recover faster.

Let’s go scenario by scenario.

Cold Weather Running: When the Air Bites Back

Cold air feels like glass in your lungs, right? That burn? That’s the cold, dry air irritating your airways. In some folks, it can even trigger a mild bronchospasm (hello, mid-run cough attack).

Here’s how to handle it like a pro:- Nasal breathing is your best friend. Your nose warms and moistens the air before it hits your lungs. Even just inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth helps.

- Cover your face. A buff, scarf, or mask traps some of your warm exhale and turns it into a mini greenhouse. Doesn’t have to be thick—even a light layer helps. Sure, it gets damp. That’s just free humidity for your lungs.

- Warm up longer. Start slow and stay nasal for the first 10 minutes. Once your core temp rises, the burn backs off. No one wins trying to crush the first mile in 10-degree weather.

- Sip something warm before heading out. Some runners swear by hot tea before a cold run. Even breathing some warm air indoors before heading out helps take the edge off.

- Cool down smart. Don’t go from sprinting to standing still in the cold. Ease into a walk, or get inside and do a few slow breaths there. Trust me—cooling down properly matters.

And one last thing: don’t let the visible breath freak you out. That fog is just condensation. You’re not dying—you’re just exhaling like a dragon.

In brutal cold (think sub-zero), shorten your run or go indoors. Your lungs aren’t made of iron.

Running in the Heat: Breathe Smart or Suffer

Running in the heat sucks. There’s no sugarcoating it. You’re drenched before mile two, your heart rate’s jacked, and your breathing feels like you’re trying to inhale soup. Welcome to summer miles.

Here’s how to breathe through the madness.

Mouth Breathing = Totally Fine

In hot, humid air, forget the nose-only purists. Mouth breathing isn’t just okay—it’s

necessary. Humid air feels thick and sticky, like trying to breathe through a wet towel. You need to get volume in, and the mouth gets the job done.

When the air’s that heavy, don’t fight it. Open up and get the oxygen however you can.

Focus on the Exhale

You’re already sweating buckets, but here’s something most folks don’t realize—

your breath helps cool you too.

Especially in humidity, when sweat doesn’t evaporate as well,

exhaling fully helps dump heat. You’re literally blowing out steam.Try slowing down your exhale, maybe even pursing your lips a bit like you’re blowing out candles. It won’t chill your core temp magically, but it can help take the edge off.

And mentally? A long exhale calms the panic. Trust me—I’ve been there.

Hydration = Better Breathing

Hot days suck water out of you faster than you think. Every breath, every drop of sweat—it’s fluid leaving your body.

Get dehydrated, and your airways dry out. Your lungs get sticky. Breathing feels like dragging air through molasses.

Solution?

Hydrate like it’s your job. Water,

electrolytes, maybe even a splash of sports drink mid-run.I’ve had moments where one swig of cold water mid-workout made my breathing feel instantly smoother. It’s not magic—it’s biology.

Heat-Induced Anxiety? Breathe Through It.

Ever feel like you’re suffocating on a hot day, even if you’re running easy? Yeah, that’s heat messing with your brain. Heart rate’s up, breath is fast, and suddenly your body’s like “we’re in danger!”

Don’t freak. Slow your breath intentionally. Use deep inhales and

long, steady exhales—same trick I use when I feel race-day nerves kick in. You’ll feel your brain chill out a bit once your breathing settles.

Don’t Try to Pant Like a Dog (During the Run)

Panting might cool you down at rest—short, fast breaths during a walk break can blow off some heat. But if you try to run while panting like that? You’ll hyperventilate and feel worse.

Instead, use

external cooling tricks:

- Dump water on your head.

- Run through sprinklers.

- Hit shaded routes or earlier hours.

Let your breathing stay natural and controlled.

Watch Out for Air Pollution

Hot days often come with ozone or

smog—especially if you’re near cities. And that stuff is brutal on your lungs.

If it’s smoggy out:

- Run early or later when it’s cooler.

- Use nasal breathing for filtering (if pace allows).

- Stick to trails, parks, or near water where air’s cleaner.

Running at Altitude: Thin Air, Big Breaths

Running at elevation is humbling. You think you’re fit… until you’re gasping like you’re breathing through a straw and your legs are jelly.

The air’s thinner. Oxygen per breath? Less. Your lungs? Working overtime.

Let’s talk survival tactics.

Pressure Breathing: Blow It Out Hard

At altitude, some runners weirdly don’t breathe enough. Sounds crazy, but it’s true. Your brain isn’t used to the thin air, and it can shortchange your breathing.

So breathe

on purpose. Try the mountaineer move: big inhale,

then blow out hard through pursed lips like you’re putting out birthday candles. It helps clear CO₂ and makes room for that next deep breath.

I’ll do a few normal breaths, then one “power breath” like that—especially grinding up a climb. It keeps me out of panic mode.

Don’t Go Out Too Hard

Don’t be a hero at elevation. If you start like it’s sea-level pace, you’ll spike your heart rate fast and risk nausea,

dizziness, or even altitude sickness.

Instead, use your breath as a throttle. If it starts racing and you’re breathing like a freight train,

ease up. Find a rhythm—maybe 2:2 or 3:2—that you can keep without gasping.

Accept the slower pace. You’re still working just as hard.

Exhale Like You Mean It

At altitude, it’s tempting to take tons of little inhales—trying to “get more oxygen.” But if you’re not

emptying the lungs fully, you’re just stacking up CO₂.

Blow it out. Then breathe in. Rinse and repeat.

Climbers have a saying:

“Empty lungs = room for air that matters.”

Same goes for runners.

Rhythmic Breathing on Climbs

Doing trail or

mountain races? You might end up breathing fast—like 2:1 fast (inhale 2 steps, exhale 1). That’s fine.

Think of it like shifting into low gear in a car—shorter cycles, more control, steady effort. Keep it rhythmic to avoid slipping into panic-breath mode.

Altitude at Rest: Freaky Sleep? Calm It Down

Ever wake up gasping when sleeping high up? That’s called periodic breathing, and it’s real.

If it hits you, do a few rounds of box breathing or just slow, deep breaths before bed. Calms your nervous system and reassures your brain everything’s fine.

Hydrate & Fuel Right

Hydration matters even more up high. Dehydration messes with blood flow and breathing. Keep fluids and electrolytes steady.

And eat some carbs—seriously. Your body uses less oxygen to burn carbs than fat. That makes a difference at 8,000 feet.

Trail Breathing Ain’t Textbook—And That’s the Point

I hate to state the obvious but

trail running isn’t like clicking off miles on a flat road.One second you’re grinding up a hill, the next you’re bombing down a rocky slope, dodging roots, catching views, and maybe even sucking wind at 7,000 feet. It’s wild. It’s beautiful. It’s also

not the place for rigid breathing rules.

So, what’s the move when the trail throws chaos at you? Flexibility. Adaptability. Awareness. Let’s break it down.

1. Be Fluid, Not Rigid

If you try to keep one perfect breathing pattern the whole time—like some 3:2 gospel—you’re setting yourself up for frustration. On a steep climb, that rhythm’s probably gonna fall apart. And that’s okay. Let it adjust. Maybe you shift into 2:2, or even start panting like a Labrador. What matters most is keeping oxygen flowing, not clinging to a strict pattern when your body’s working overtime.

2. Let the Terrain Guide You

Here’s a simple cheat sheet I give my runners:

- Flats? Settle into a smooth rhythm like 3:2. Think “cruise control.”

- Uphills? Power breathing. Strong exhales, maybe even a good ol’ grunt to push you through.

- Downhills? This is your breathing recovery zone. Downhills aren’t as aerobically intense (unless you’re sprinting), so dial it back. Maybe go back to nasal breathing here to calm things down.

Got a sketchy technical section? Like hopping over boulders or balancing on a ridge? A lot of folks instinctively hold their breath while focusing. Don’t. That’s how you drain your brain and tighten up. Keep a soft inhale-exhale going—even while dancing over rocks. Oxygen = better balance and focus.

3. Dealing with Altitude?

If your trail climbs into thinner air, don’t wait until your lungs are burning to change gears. Start breathing deeper and slower early on. The higher you go, the more deliberate you need to be. Controlled breathing helps offset that gasping feeling you get in thin air.

4. Find Your Own Flow

Some trail runners breathe like cyclists—short bursts uphill, big resets on the flats. It’s not a mistake. It’s just real-life adaptation. You might power-hike a ridge and nose-breathe to recover, then hammer the descent with deep, steady exhales. Whatever works for

you—as long as you’re aware and not just holding your breath out of habit.

5. Don’t Forget to Look Up (And Breathe It In)

Yeah, the views can take your breath away—literally. But if you gasp at a sunrise over the valley, just follow it with a deep, calm exhale. There’s actual science behind nature relaxing the body and slowing your breathing rate. So don’t be afraid to let that scenery work its magic on your nervous system.

Trail Tip Recap:

- Cold air? Breathe through your nose or use a buff/scarf to warm the air.

- Heat? Expect faster breathing. Stay loose, hydrate, and don’t panic if your breath rate is up.

- High altitude? Focus on long exhales and slower, deeper breathing.

- Trail chaos? Be loose, adjust on the fly, and keep breath awareness sharp.

Bottom line: The trail doesn’t follow rules—and neither should your breathing. Learn to roll with the terrain and your lungs will learn to keep up.

Coaching Yourself Through Breath Fatigue

Let’s be real—no matter how dialed your training is, there’s gonna be a point in a hard run or race where your breathing turns ugly. You’re gasping, your brain’s begging you to stop, and you’re wondering why you ever signed up for this nonsense.

This is where most runners crack.

But you? You’ve got tools. You can coach yourself through it.

Let’s break it down. Here’s how to self-rescue when the breath goes sideways.

Cue Words: Short, Simple, Lifesaving

When things get rough, you don’t need a pep talk—you need a lifeline. That’s where cue words come in. Just a few choice words that hit like mental reset buttons.

Here are a few I swear by (and have used mid-sufferfest more times than I care to admit):

- “Soft jaw.” Weird? Maybe. Effective? Hell yes. Most of us tense our face when we’re hurting—clenched jaw, tight shoulders. Saying this chills you out instantly. Loose face = loose breath.

- “Belly.” If your chest is doing all the work, you’re shallow breathing and making things worse. Say “belly” to yourself and shift that breath lower. More oxygen, less panic.

- “Out… out…” Most runners panic and suck in air like they’re drowning. But what you really need? A solid exhale. Blow off that CO₂. Make room. I’ll literally think “out… out…” on repeat when I’m wheezing. It slows me down—in a good way.

- “Rhythm.” When your breathing’s all over the place, this cue helps get things back on beat. Aim for a 2:2 or whatever feels doable. Doesn’t matter the exact ratio—just find your breath again.

- “Relax” on inhale, “Release” on exhale. Or use whatever mantra works for you—“Calm / Power” or “I am / Strong.” Yeah, it might sound cheesy reading this now. But mid-race? These mantras slap.

Practice these in workouts so they’re second nature. When race day comes and things start unraveling, you’ll have a script ready to go. Inner chaos needs a counterpunch—and cue words are just that.

Walk Breaks: Not Quitting—Resetting

Let’s kill the ego talk: walk breaks aren’t weak. Sometimes, they’re your best move.

If your breathing is totally shot and your form’s falling apart, a 15- to 30-second walk—done with intention—can reset the whole system.

Here’s what I coach runners to do:

- Shoulders back.

- Big nose inhale, belly expands.

- Mouth exhale like a sigh—force it out.

- Maybe shake out your arms, get loose.

This is

active recovery, not defeat. You’re choosing to walk. That mindset shift matters. And you bring that calm, controlled breath right back into your run.

I know runners who crush

half-marathons by walking through every aid station to reset breathing. They finish faster than folks who try to “tough it out” and crash at mile 9.

So take the walk. Use it. Then rally.

Breath Isn’t Failure. It’s Feedback.

Here’s a mindset shift that’ll change how you handle the tough stuff:

Heavy breathing doesn’t mean you suck.

It means you’re working.

Even elite runners are breathing like freight trains at

race pace. That’s not weakness—that’s just how effort shows up.

So when your breath gets gnarly, don’t spiral. Get curious. Think:

“Okay, I’m redlining. Do I hold this or back off slightly and regroup?”

That one second of decision-making gives you power. You’re not just surviving—you’re coaching yourself in real time.

You’ll start to

read your breath like a dashboard gauge. “Lungs burning? Good. Training effect is happening. I’m leveling up.”

Of course, if you’re dizzy or seeing stars? Back off. Don’t be a hero. But 90% of the time? It’s just discomfort. You can handle it.

Know When to Push… and When to Pull Back

This is the art of self-coaching.

Let’s say you’re in mile 5 of a 10K and your breathing’s getting ragged. What do you do?

- Check your form. Are you collapsing forward, shoulders up to your ears? If yes—reset. Cue that soft jaw. Loosen up.

- Check your brain. Are you panicking? If yes—get back to rhythm. Mantra up.

- Still holding decent form, and you’re near the finish? Push through.

- Still got miles to go, and you’re unraveling? Ease back 10 seconds per mile. Catch your breath. Regroup. Rally.

Another trick I use: give yourself a mini checkpoint.

“Hold this effort for 1 more minute. Then reassess.”

Often, you’ll stabilize. Or at the very least, you’ll delay the panic spiral. And by the time that minute’s up, your brain’s clearer and you’re in control again.

You’ve Got More Tools Than You Think

Being your own coach doesn’t mean ignoring warning signs or going full Navy SEAL on every hill. It means

managing the chaos.

Try nasal breathing. Didn’t help? Walk it out. Still struggling? Try cue words. Or rhythm. Or focus on form. You’re not stuck. You’ve got options.

There’s power in that.

Your Breathing Coach Checklist (That’s You)

To coach yourself well, here’s what you need in your back pocket:

- ✅ A solid set of breathing cues and drills (like crocodile breathing or balloon work)

- ✅ A clear head — don’t freak out mid-run, ask: “What can I adjust right now?”

- ✅ The guts to slow down strategically so you can finish stronger

- ✅ Positive self-talk — not “I suck,” but “Let’s reset and find that rhythm again”

You master this, and boom — you’ve got a personal coach with you every run. One who knows you better than anyone.

Pair that mindset with the physical breath work? You’re building one heck of a resilient runner.

Race-Day Breathing Strategy

The gun goes off. Nerves kick in. Adrenaline’s pumping. And guess what? This is where having a breathing strategy gives you an edge.

You plan your pace. You plan your gels. Why not plan your

breathing too?

Here’s how to stay in control from the first step to the finish line.

Pre-Race: Prime the Engine

Warming up your legs is obvious. But your lungs? They need love too.

About 10–15 minutes before go-time, after your jog and drills, throw in a few deep breaths — maybe even a breathing drill or two. This helps shake off those shallow “nervous” breaths.

I like tossing in a few

60-meter strides at race pace to get the breath moving — then walking for 30 seconds, taking deep, steady breaths. Feels weird, but it helps big-time. You won’t be shocked by that first surge when the race starts.

Too jittery? Try box breathing or 4-7-8 for a minute. Works wonders. Excitement is great — use it — but don’t let it run the show. You’re in charge.

First Mile / 1–2K: Use Breathing as Your “Effort Gate”

Here’s a lesson I learned the hard way —

run the first part of your race by breathing, not by pace.

Seriously. That start line hype makes everyone fly, and unless you’re careful, you’ll redline before the race even begins.

Check your breathing. Are you gasping already? That’s a red flag. Ease off.

In a 5K, you might hit 2:2 breathing early on. That’s okay. But if you’re at 1:1 right out the gate? Yikes. Back it down.

For longer races — half or full — you should still be in that comfy zone. Nasal breathing or light mouth breathing.

Zone 2 or low Zone 3. If you can mutter “good luck” or whisper your mantra, you’re golden. If not? You’re going too hard, too soon.

Pro tip: Do breath checkpoints early. At 400m, do a form + breath scan:

- Am I breathing through my nose or mouth?

- Is my breathing smooth or ragged?

At 1K or 1 mile — check again. Still under control? Great. Getting panicky? Slow just a touch. Sacrificing 10 seconds now can save you 3 minutes later when everyone else is falling apart.

Breathing gives you a read on effort, especially around threshold pace. That’s the sweet spot in halves and early in longer races. Nail that, and you’ll be set up for a strong second half.

Mid-Race Breathing – Regroup, Reset, Keep Charging

Alright, this is where the race gets real. You’re deep in the middle miles — too far from the start to still feel fresh, but not close enough to smell the finish yet.That’s when fatigue sneaks in, your breath starts getting heavier, and your brain starts whispering trash like,

“You’re already tired? Yikes.”

Here’s the fix:

use your breath to fight back.Reset on the Fly

First sign of spiraling? Take control. I’ve been in races where I felt like I was unraveling at mile 4 of a 10K. What helped? A quick breathing reset. Try this:

- Two or three deep, focused inhales

- Forceful exhales (like blowing out a birthday candle that just won’t quit)

- Bonus: do one of those breaths through your nose — it’s calming and settles the chaos

It’s like hitting a mental “refresh” button.

Tip: Try this on a downhill or flat section where you can afford to focus on breath for a few seconds without losing momentum.

Downshift, Then Rebuild

You ever grind up a gear too long in a car and it just screams? Same with your breath mid-race. If you’re wheezing like a busted accordion, it’s time to downshift:

- Ease your pace just slightly for 10–20 seconds

- Lock into a 2:2 breathing rhythm (inhale for 2 steps, exhale for 2)

- Shake out your arms, drop your shoulders — get loose

- Once you feel your breath return to “manageable,” step back on the gas

That little adjustment can save your race. It’s a small price to pay now to avoid a big crash later.

Play the Terrain

Hills? Time to shorten that breath pattern and focus on exhaling during the hard pushes.

Downhill? That’s your recovery lane. Keep moving fast, but use it to catch your breath — deep, rhythmic inhales, full exhales. Let gravity help you reset.

Make the course work for you, not against you.

Break the Race into Breathing Zones

This one’s a game-changer. Don’t think of the race as one giant block of suffering. Slice it up and assign a breathing plan to each part.

For example, in a half marathon:

- Miles 0–5: Easy nasal or 3:3 pattern. Chill mode.

- Miles 6–10: Shift to 2:2. Strong but steady.

- Final 3.1: Let it rip. No rules, just grind.

Having this plan means you

expect the breathing to get harder — and when it does, you’re not panicking, you’re saying “Yep, I’m in phase two. Game on.”

The Final Push – Breathing in the Pain Cave

Alright, final 4–5 minutes. This is the do-or-die stretch. You’re not trying to stay smooth here — you’re trying to finish strong.

Let It All Out

This isn’t the time to be dainty. Mouth wide open. Chin slightly up if needed. No shame in sounding like a winded gorilla here — you’re giving it everything.

Focus on

big, full exhales — don’t hold anything back. Every drop of stale air out means more room for fresh oxygen in. You might grunt. You might growl. That’s fine. You’re racing.

Use Mental Tricks

If your breath feels like it’s going off the rails from adrenaline or the crowd screaming, fire off a sharp

“HAH!” exhale — martial arts-style. It resets your rhythm and focus instantly.

Then count your breaths. “Ten more big breaths. Then I’m done.” Totally arbitrary, but it works. It gives your brain something to grab onto when everything else is chaos.

Cross the Line with Intent

As soon as you finish, don’t just crumple and pant. Get some control back:

- Long exhale

- Hands on head or bend over — whatever lets your diaphragm move freely

- Try nasal breathing as soon as you can — even if it’s just a sip through your nose to start calming the system

Keep walking. Keep breathing. You’re not done till you’re back in control.

Post-Race Breathing – The Recovery You Forgot You Needed

Most folks think the race ends at the finish line. But how you breathe in those first 60 seconds after stopping? It can make or break your recovery.

If you’re gasping:

- Keep moving — slow walk

- Deep inhale through your nose

- Long, steady exhale through the mouth

- Do a round or two of box breathing (4-4-4-4) if your nerves are buzzing

Avoid shallow, fast panting — it’ll just make you feel lightheaded or sick. Slow it down, one breath at a time.

Recap – Your Breath is the Real Pacer

Forget all the splits and

fancy watches for a second. On race day,

your breath is your dashboard.

Start breathing too hard, too soon? That’s your warning light. Ignore it, and you might blow up. But if you respect your breath — if you listen to it, adjust, and use it like the tool it is — you’ll stay in control.

Flip the Script

Contrary to what most people do, don’t fixate on pace or the runner in front of you. Lock in on your breathing — especially early. If you stay calm, you’ll pass them when it counts.

Negative split runners always say the same thing:

“I kept my breathing steady early on, and I had gas left at the end.” That’s not luck — that’s breathing discipline.

Race Breathing Plan — Keep It Simple, Keep It Strong

Here’s one you can use (or tweak your own):

- First mile: Nasal and easy — just settle in

- Middle miles: Dial in rhythm — monitor, adjust, don’t panic

- Final stretch: Let go — push hard, breathe harder, leave nothing behind

The point is to take out the guesswork. If you’ve got a breathing plan, you don’t have to make decisions when your brain is cooked. You just run the script. And that edge? It’s real.

Final Words – Breathe Like It Matters (Because It Does)

Take a second. Yeah—right now. Inhale deep through your nose… now exhale slow through your mouth.

Feel that? That’s not just air. That’s power. That’s calm. That’s

you taking charge.

We’ve covered a lot in this guide. Drills, mechanics, science, apps, mindset… all the tools. But here’s the bottom line:

Your breath is not background noise. It’s one of the most underrated tools in your running toolbox—and it’s always with you, free and ready to go.

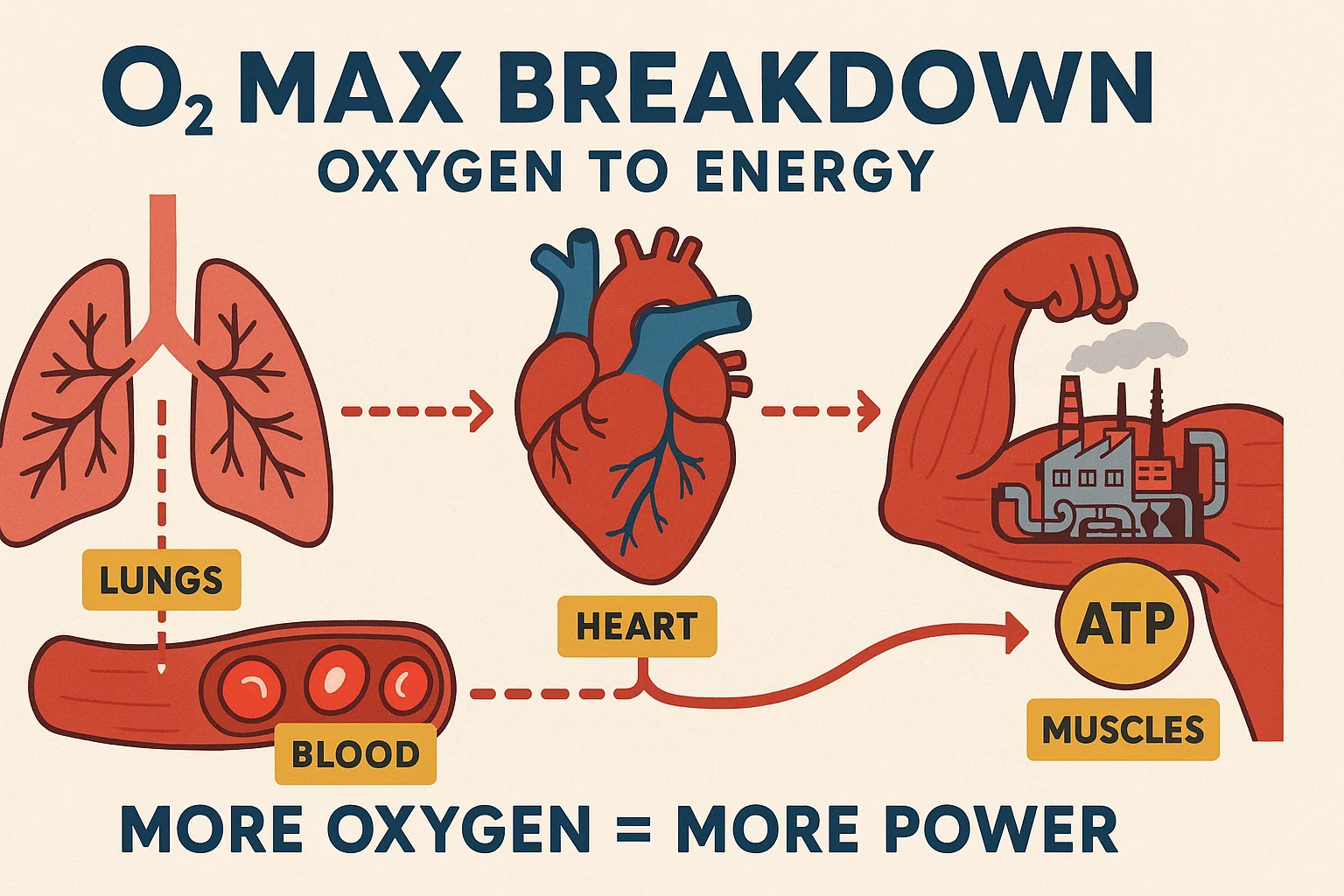

Breath = Power

Oxygen is your fuel. And how you breathe decides how much of it gets delivered to your working muscles. If your breath is choppy, shallow, or rushed, you’re basically feeding your engine through a straw. But when you breathe right—using your diaphragm, settling into a rhythm—you’re pumping high-grade fuel straight to the legs.

And here’s the kicker: with drills like CO₂ tolerance work, you’re actually raising your threshold. You’ll be able to go harder, longer, and not freak out when your lungs start screaming. That’s real power.

I’ve coached runners who cut 30 seconds per mile just by getting smarter about their breathing. Not by training harder. Just by training wiser.

So yeah, breathwork might not look as tough as hill sprints or track reps, but don’t sleep on it. This is strength training for your respiratory system. Take it seriously, and it’ll pay you back with faster paces and smoother runs.

Breath = Calm

Let’s be honest—running can mess with your head. You get anxious before races, overwhelmed on long runs, or just plain stressed by life. But your breath? That’s your anchor.

It’s the switch that flips your nervous system from fight-or-flight to

chill and focused. You saw how anxiety and poor breathing feed each other in a vicious cycle. But when you slow the breath—especially those long exhales—you break that loop.

I’ve had runners turn around an entire workout just by stopping mid-run, taking 3 deep breaths, and starting fresh. That’s the kind of tool you want in your back pocket.

And let’s not forget the magic of a peaceful solo trail run, early morning, nobody around. Slow your breath and really

feel the run. It becomes something more than exercise. It becomes therapy.

Breath = Focus

Ever zoned out mid-run and

lost your form? Or spiraled into

negative thoughts—“I can’t do this, I’m done”?

Your breath can pull you back.

Use it like a metronome. Inhale 1-2, exhale 1-2. Lock into a rhythm and let it guide your steps. In a race, this can be the difference between staying strong or falling apart.

And when your mind starts whining? Drown it out with breath count. No room for “I’m tired” when you’re focused on “Inhale… Exhale… Inhale…”

That’s what I call breathing with purpose. It keeps your brain from quitting when your legs still have more to give.

Train It. Use It. Own It.

Mastering your breath isn’t just about getting better at running—it’s about mastering

yourself. Turning something automatic into something powerful.

So what now?

- Make breath training a habit. Put a sticky note on your mirror that says “Breathe deep.” I’ve got one on my fridge.

- Pick one drill and try it this week. Nasal breathing during your easy run. A long-exhale cool-down. Breath holds on the couch.

- Have fun with it. Try “Mouth Tape Monday” or “Nasal-Only Wednesdays.” Make it a game.

- Track your wins. Notice when you recover quicker, nail a hill you used to dread, or feel calmer pre-race. These moments matter.

This stuff compounds. One day, you’ll realize you just crushed a route that used to leave you gasping—and your breathing never went sideways. That’s progress.

So remember this:

your breath is your training partner. It’s with you on every run. Treat it like an ally, not an afterthought.

Train it. Trust it. And let it unlock a new gear in your running.

Now… take one last deep breath.

Inhale.

Exhale.

Time to run with power, calm, and focus.

Let’s go.